You may have noticed that urbanists have been obsessed with Tokyo lately. Lots of people want to talk about Tokyo’s housing, its dense and narrow streets, its overall vibrancy and how this megacity could be a model for the U.S. (We can dream!)

Well, here’s one more reason to consider Tokyo the vanguard for cities.

In April, Japan’s largest employer, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, decided to tackle two interrelated issues — the country’s declining fertility rate and its ultra-intense work ethic — by testing out a new policy for its 160,000 government workers: the 4-day workweek.

The hope is that once people have a better work-life balance they’ll start to form or grow their families. Japan’s birth rate hit a record low in 2024 after nearly a decade of decline.

Though the city isn’t cutting workers’ hours — it’s compressing 40 hours into four days per week — it will significantly reduce the amount of weekly commuting time. Tokyo’s average commutes exceed many of those in the U.S. at approximately one hour each way. And many people in Tokyo already work 10-hour days, so for them it will be like a full extra day off each week.

While most of Japan is back to in-person work, remote and hybrid work have remained popular with professional services industries, particularly in Tokyo. This policy could help Tokyo’s government attract and retain workers who might otherwise work for the private sector. But according to the government, that’s not the goal; for them, the best case scenario is that this move influences private sector employers to also adopt four-day workweeks.

Meanwhile in the United States, many city governments have adopted a strong back-to-the-office policy. Last summer, Philadelphia Mayor Cherelle Parker was the first head of a major city to successfully implement a full five days in person back in the office — in the middle of the summer.

Perhaps thinking this would be easy, San Francisco Mayor Dan Lurie called his city’s workers back to the office four days a week with one remote work day starting April 28. But after receiving intense pushback from an employee union, he set a new start date in August for the policy.

These battles over in-person work reflect the conflicting priorities of individuals, local economies, and societies writ large.

Individuals struggle to find enough time to be fully engaged in both their work and their families and see remote work as a way to multitask across multiple domains, often at the same time. Yet, as a recent Gallup study suggests, often fully remote work is a sure path to a less thriving life.

Local economies still need people to take transit, go shopping, and eat out in order to survive.

And societies need people to work in person for more existential reasons – to maintain a shared reality where in-person connection fosters some degree of social cohesion.

For most mayors and CEOs, the easiest solution to this problem is to ask for everyone back in the office all the time. Cue the disgruntled workers, the lawsuits from workers, the resignations.

But instead of five days a week in the office, the four-day office workweek might be the perfect compromise and one that allows everyone to get just enough of what they need to be satisfied. This is the thinking of Philadelphian Julian Plotnick, who is on a mission to encourage more companies to institute the four day workweek — though in his case it would be 32 hours — through his organization, 4 Day Philly, which itself is part of a national movement. “It’s good for the culture of companies: You trust employees to be adults, and they’ll give more effort,” Plotnick says.

Here are three good reasons why a four-day workweek is worth considering, particularly for local governments.

Cities are now doing better on weekends than weekdays. So expand them

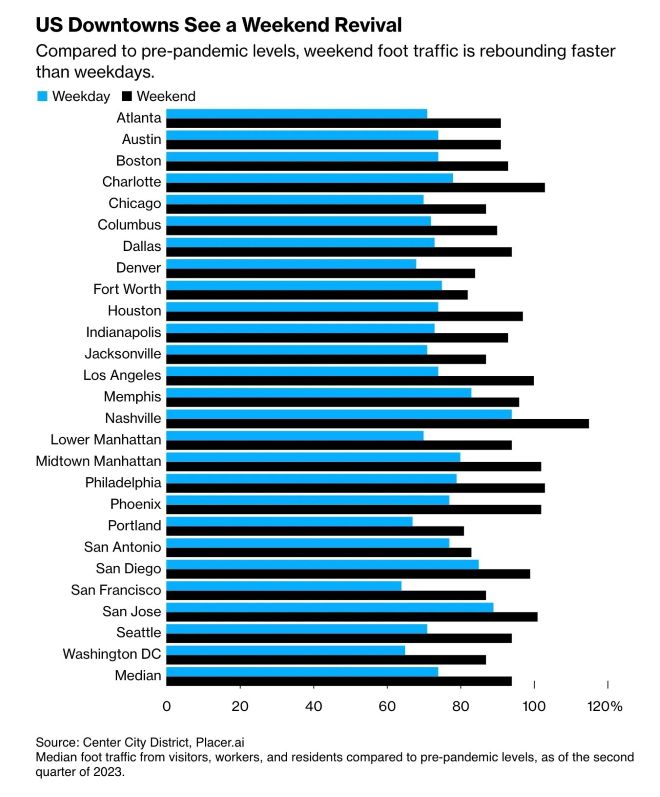

Perhaps the top reason to move to a four-day work week is that cities have seen their post-pandemic foot traffic recover to or even exceed 2019 levels on weekends, while foot traffic on weekdays often has plateaued around 70 percent for most cities. And it’s not just foot traffic: Transit agencies, such as California’s Metrolink, are setting ridership records on the weekends.

If our weekends are so successful, why not expand them with an extra day?

When people have free time away from work, they are actually enjoying our cities, running errands, and getting stuff done in person. With an extra weekend day, we have more days to enjoy the events that are driving much of our economy.

If we want our downtowns to thrive, we should actually be pushing for more weekend days rather than just more employees in the office. Besides, the AI-will-take-your-job stories are getting more frequent these days. Build your non-knowledge-work economy sooner rather than later!

Four strong days in person might be better than five weak hybrid days

Hybrid might be the worst of all worlds for local infrastructure. Can public transportation continue to run rush hour schedules in a country where 28 percent of all work days are now remote? In places such as Philadelphia, there is the threat of major service cuts to deal with the financial fallout from decreased ridership. Because commuters’ work schedules have become less predictable with hybrid work, transit agencies still need to run trains and buses to maintain adequate service, but they are more likely to be running at less than full capacity now. If the workweek was more rigidly Monday through Thursday, transit agencies might have more predictability for their ridership and adjust accordingly.

Additionally, if you’ve ever worked in a hybrid workplace, you know that it can also be difficult to get a quorum of people in person for meetings or even for casual interactions. Every meeting becomes a hybrid meeting where people join in person and on Zoom, and reducing the predictability of knowing whether you’ll connect with people face to face or not. A shorter — but more purposefully in-person — workweek would not only restore the priority of connecting in person, but ensure people get the full social benefits of going into the office. Let’s save Zoom for meetings with people outside our immediate workplaces, not use it to accommodate misaligned hybrid work.

Four-day workweeks don’t have to reduce economic growth

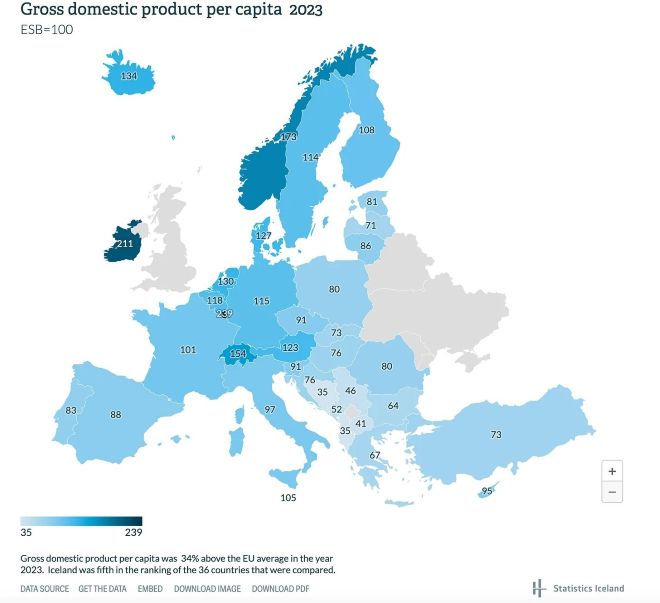

Experiments in Belgium, Spain, the UK, and other parts of Japan have also told the same story: working four days doesn’t reduce productivity or reduce economic growth. Iceland, where today 90 percent of employees work four days per week, has a GDP that is apparently 34 percent above the EU average.

Iceland is the only one of these countries that didn’t just compress the work schedule, but actually reduced work hours to just 36 hours per week. Notably, the reduction in hours worked has led to an increase in the share of housework done by men.

Indeed, a main driver for the four-day work week in Japan is the hope that a four-day workweek can help balance not just life and work, but the domestic load between men and women. (And coincidentally, that domestic load is a main reason why so many women prefer remote work, so this is another route to encourage in-person work.)

Surveys have found that women do five times as much housework there as men. (In the U.S., women do about twice as much.) No matter what you can say about Tokyo’s amazing housing and urban fabric, that dismal statistic definitely needs to change.

Diana Lind is a writer and urban policy specialist. This article was also published as part of her Substack newsletter, The New Urban Order. Sign up for the newsletter here.

![]() MORE FROM THE NEW URBAN ORDER

MORE FROM THE NEW URBAN ORDER